David A. Mundie on Cooking and Technology

David A. Mundie in his little book "Computerised Cooking" introduces RxOL, the first programming language for recipes, and also Cocina software for Macintosh that uses it. In 1985.

Cocina can print recipes as a tree diagram, display nutritional analysis of the recipe, create shopping lists and much more.

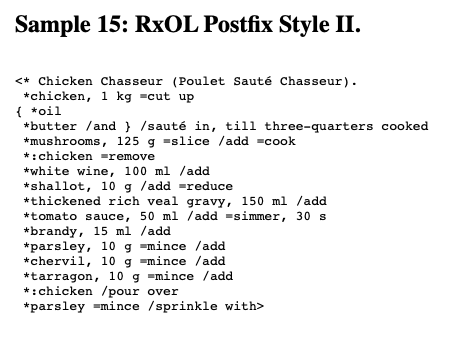

The recipe format uses reverse Polish notation (it's when we use operator after operands 3 4 + = 7). The genius of it is that allows us to describe graphs in text format. Absolutely brilliant, but hard to read...

Next is the interview with David A. Mundie I did in 2024.

RxOL

- What originally inspired you to create RxOL?

DAM: At the time I was a student of French literature and a huge fan of Claude Levi-Strauss and “The Raw and the Cooked”. The quasi-mathematical frameworks in that work, which provided a rigorous philosophical basis for gastronomy, were the principal motivation for RxOL.

His format didn't have anything to do with what I came up with. It was just obvious to me that reverse Polish notation was the right way to go, because it's compact, and it's formal, and it's easy to process. And there are tools available for it.

I didn't spend too much time thinking about that. In retrospect, the average cook is not ready to talk about reverse Polish notation. But it's unambiguous, and it's very sad that I'm the only person on the planet that writes recipes [in that format]. And over the years, I have collected quite a lot. That is a major obstacle, obviously, because it's very slow to do that translation. And so actually, now that you've brought that up, maybe that's a good role for AI.

My goal was to make the traditional recipes that have been tried and true in such a way that average people can make these dishes.

That, to me, is the real challenge is getting people to stop eating Big Macs and fast food and actually eat more interesting dishes. And so that was my goal: to streamline the process of going from the recipe to the execution of the recipe as quickly and easily as possible.

- Why do people choose Big Macs over cooking at home?

DAM: Celebrity chefs like Julia Child are the big enemy here. She is the person that I blame for this because you look at her cooking shows and the number of complications that she adds into the recipe make it unappealing. Nobody would actually cook that way.

But, you know, a Coq Au Vin is a Coq Au Vin. You shouldn't clutter the recipe. That's one of the things I think I said in my essay, that you want to separate the commentary, you know, oh, my grandfather used to make this and blah, blah, blah, that impedes you from getting in touch with the recipe itself.

If you have a new recipe that you want people to try, I don't think you should surround it with five pages of autobiography. It just irritates me to no end.

- Ah, that's why in RxOL a regular recipe is reduced to bare minimum...

DAM: Oh, sure, absolutely. I'm not suggesting that we should just throw out everything except the ingredient list. But I'm saying that for me, the ingredient list is all I really need. It depends on the recipe [of course]. If it's a really weird recipe with ingredients that I've never heard of before, then I need to go look at the recipe.

But I'm saying that on a day-to-day basis, I don't really have that much need for the complete recipe. And that goes back to what I was saying about Julia Child, that I think that the recipe should be clean and simple and understandable without all of that background text.

- What's the best way for someone with no cooking experience to start learning?

DAM: Give them a plane ticket to Bordeaux. And have them take a class at the Culinary Institute of Bordeaux. But seriously, I think that there's something to that. You need to start with a cook that knows what they’re doing. And you learn by imitating. But again, you want it to be a cook that is doing practical stuff, not in an elaborate way.

And I don't know how to find such an instructor. I remember a number of people that I have learned from. And what I took away from it, was that you don't want somebody who is a prima donna that takes pleasure in making it seem as complicated as possible. You want a practical, practicing cook who is not working at a McDonald's.

There's this enormous heritage of recipes and culinary processes and so forth out there that I'm afraid is disappearing pretty rapidly. And I think we should try to capture as much of that. And fortunately, I have some cookbooks that I inherited from my grandmother. They're really old-fashioned recipes and cookbooks. But some of them are excellent.

I think there are a number of different sources for getting recipes. And you should treasure that.

- What was the world of computers back in 1985?

DAM: My first recipes for computerized cooking were printed out on teletypes. I found somebody who was selling a used teletype machine and that's how I printed out my recipes. I had a teletype machine because I couldn't afford anything else. I should have saved some of those.

Teletype machines were what people used to communicate in news bureaus, that's how they got their news. They sent it to everybody by teletype. It was like a typewriter, but with a computer interface.

I dumped the teletype machine when the Macs came out, I was one of the early customers for the Macintosh. And it's just incredible how primitive they were.

- How was the reception of your essay when it was published?

DAM: There practically was no internet back then. I emailed it to a few of my friends. And the best reception I got was a friend of mine who made fun of it and said, oh, this is silly. But then at the same time, he recognized that this is a good thing.

There's a lot of inertia, a lot of culture surrounding the traditional ways of doing that. And to ask somebody to step outside that paradigm... And also, I just didn't care enough. I had it for my recipes and it would have been nice to get more recipes in RxOL. But it wasn't enough of an obstacle. I can still cook just about anything I want.

That's what I see as being the major advantage of AI, is to be able to do intelligent searching for recipes. Because just entering them all and then being able to search them, that's a major project, no matter what the format is. And especially because the copyright industry makes that as difficult as possible, in my experience.

Unfortunately I’m not much of a salesman. It’s much more fun to think about recipe theory than to market it. Once I had reached a level of completion for my own purposes, I didn’t feel as much pressure to take it commercial.

- What are the main benefits for you in using RxOL?

DAM: The ability to scan a recipe and take it in at a glance and understand its structure. I have one big folder that has everything in it. The filename is just the name of the recipe, dash, Dewey decimal code. I have a random recipe generator that spits out an unlimited set of recipes. I pick out four recipes for the week and generate the shopping list from that.

About cooking and technology

- Looking back, how do you feel about the progress we've made since your essay was published? Are there any technological developments in the kitchen that have surprised you? What were some of the limitations of the technology at the time, and how did you imagine they might evolve?

DAM: Really nothing that moves us closer to automated meal preparation. Cooks today use pretty much the same tools and techniques as cooks in 1985. I enjoy dreaming up new flavor combinations and new ways to process ingredients, not the drudgery of implementation.

I am a complete skeptic when it comes to AI. I hope I’m wrong, but I also think we are far from the day when we can simply say, “Hey Mr. Culinary Robot, please generate 15 French recipes that call for Belgian endive, game hens, and cream” and have it spit out something usable.

I don’t think the torrent of amateur, haphazard recipes will taper off. There will continue to be the occasional serious time like Marcella Presilla’s Gran Cocina Latina. People will continue to collect cooking equipment such as Instant Pots which for the most part will sit unused at the back of the closet.

The one thing that I always thought was just around the corner and that would make everybody's life a lot easier is the Vitamix, the real Vitamix. Vitamix is a blender, but it's a little bit more than that. It claims to do a lot of different things in the kitchen.

And I had always assumed that in my lifetime, we would have robots that would do the preparation for us. But that never happened. And that's OK, I guess. But it's still a nice dream. And it's a nice way of thinking about cuisine and computers that, to me, the goal still is to have a robot that does what I do in the kitchen so that I don't have to stand there peeling the potatoes and so forth. But I just don't see the market for it.

Instapot is a glorified pressure cooker that came out, oh, I don't know, five, six years ago. And it's a nice machine, but when all is said and done, it's just a pressure cooker. And we have pressure cookers, and so it's not.

They want you to think of it as a complete revolution in the kitchen, but it's just a pressure cooker.

I stopped accumulating culinary instruments along the way. I forget why, but none of them did enough of the cooking for you to make the overhead worthwhile.

No, but I haven't given up. I still think there's a market, and you could make a lot of money if you could really come up with a machine that did what humans do in the kitchen. But we're not there yet.

- What would your expectation be? You just do nothing, and it will produce a dish?

DAM: Do all the chopping. I think that with all the individual steps, you can imagine being able to do them.

Asking a robot to chop a carrot is at the limit of what we can imagine, because you've got to worry about the ends. It's got to be able to identify where the ends are and do a good job of holding the carrot and moving it up a certain distance and chopping.

But you can imagine that happening. The Vitamix comes about as close as it. I've used the Vitamix, but reading their literature, they claim to have solved some of that problem.

- I've always been fascinated by the agricultural machines used for harvesting. They're incredibly complex and seem almost magical in how they work. Maybe we could adapt their technology for other uses?

DAM: Things like picking grapes is a challenge for harvesters, but they're doing it now. The progress they've made in harvesting things, because they have had to tackle the temporal aspect of harvesting. They've tried by choosing the right variants, the right seeds to make it so that all the fruit on a grape plant ripen at the same time.

But that's still not perfect. And so you need some way for the robot to assess whether this group of grapes is ready to collect or not. So I don't see any real obstacle, except what we at the Software Engineering Institute called an SME, a small matter of engineering, which, of course, is always the hard part.

It's engineering. But conceptually, I think that it's clear enough where we need to go. There are a number of problems that we need to solve along the way, but I think we'll get there. If there's some financial motivation.

- What advice would you give to today’s innovators in the intersection of technology and cooking?

DAM: Try to steer a course between ridiculously complicated and pretentious recipes on the one hand, and recipes with nothing new to offer.

Another thing is to take seriously the notion of a culinary robot and look at what is feasible, what's not feasible, what the problems are. My suspicion is that there are simple ways to cut down on the complexity of the recipes. Even simple things like take the ingredient list and chop the carrots. It's a lot easier to cook when you just have a pile of the ingredients and throw them one in after the other.

So if I were giving advice to somebody who wanted to get into this business, that's what I would do, is look at case studies taken from HelloFresh like companies, and see what went wrong, why everybody isn't doing it, and how you can improve the process.

1st December 2024